"Antimins under the open air." An article about the Kazakhstan new martyrs and confessors, published in the

- 25.01.2024, 14:26

- Новости на английском языке

More than two hundred people were canonized. There are much more of those who suffered for their faith during the years of atheism on Kazakhstani soil and were not glorified. His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II, visiting Kazakhstan in 1995, called this long-suffering region “an antimins, spread out in the open air.” In the ancient Turkic steppes, where in the past there was not a single revealed saint, thanks to the suffering of many bishops, priests, monks and laity, the Church of the Martyrs and Confessors of Kazakhstan was born, which is called in the service dedicated to them “The Desert Bride of the Lamb of God.” The article was published in the «Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate» (No. 12, 2023, , PDF version).

First martyr on the lands of Kazakhstan

Bishop of Semirechensky and Vernensky Pimen (Belolikov) was appointed vicar of the Turkestan diocese in July 1917. He was warmly welcomed in the city of Verny (until 1921 this was the name of the city of Alma-Ata) by the clergy and townspeople. The Bishop resumed Sunday afternoon readings for parishioners at the People's House, at which he spoke about the disasters of the revolutionary times, explained the danger of atheistic ideology and the lawless transformations that took place as a result of the coup. In connection with the elevation of Saint Tikhon (Bellavin) to the Patriarchal throne in December 1917, Bishop Pimen convened a congress of the Vernen clergy in his bishop's chambers, dedicated to understanding the significance of this event.

After the establishment of Soviet power in March 1918, the Civil War began in the city of Verny. The archpastor organized a church procession with icons and ringing bells and himself stood at the head of it, heading with the people to the location of the Cossacks, where he served a prayer service and called for peace. On Bright Week 1918, he led two more mass religious processions from the city's cathedral to the churches of the Cossack villages with a call for peace. The Vernensky bishop at the same time set an example of true civic responsibility by organizing assistance to starving children.

Vladyka Pimen was inconvenient for the new government. He condemned the decree on civil marriage adopted by the Bolsheviks, advocated the preservation of the teaching of the Law of God in schools, defended church values during their confiscation in the summer of 1918.

On September 16, 1918, the bishop was arrested by Red Army soldiers of Ivan Mamontov’s punitive detachment, without trial or investigation, was secretly shot on the same day in the Baum Grove outside the city. The news that the bishop had been arrested instantly spread throughout the city. The ruling Archbishop of Turkestan and Tashkent, turned to the Bolshevik authorities with a request for the bishop’s location. Representatives of the Semirechensk Executive Committee, trying to hide the fact of arbitrariness, published an order in the “Bulletin of the Semirechensk Working People” with false information, interspersed with threats to all sympathizers: “For counter-revolutionary actions against Soviet power and as an enemy of the working people and the peasant poor, Bishop Pimen is subject to expulsion from the Semirechensk region, which was fulfilled on September 16. All supporters, defenders and henchmen of the exiled counter-revolutionary bishop Pimen are declared counter-revolutionaries and will be punished using wartime measures.”

It is still unknown where the bishop was buried. At the site of his death, believers immediately began to gather for prayer - first secretly, then openly. In 1998, on the 80th anniversary of his death, a granite obelisk was erected at this mournful place. In 2000, at the Jubilee Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, Bishop Pimen of Semirechensk and Vernensky was glorified in the Council of New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church. The day of his martyrdom - September 16 - became the day of his veneration. On the first Sunday after this date, the celebration of the Council of New Martyrs and Confessors of Kazakhstan was established. And now, every year on this autumn day, many clergy and parishioners, led by Metropolitan Alexander of Astana and Kazakhstan, gather in the Baum Grove to offer prayer to the Hieromartyr Pimen.

Bishop's Asylum

From the late 1920s to the 1930s, Alma-Ata became the largest transit point of the GPU NKVD, where prisoners arrived from all over the country. From here, having received distribution to camps or exile, they were sent further along the stage. While people were waiting for directions, they needed somewhere to settle down. There was no hope that they would be taken to live in apartments, since the local population was intimidated. They found shelter in the St. Nicholas Church. One of the oldest churches in the city, built in 1908 in the Kuchugury area, was destined to become a saving monastery for persecuted and tormented people. During the services, the temple was crowded with believers, the altar was filled with clergy, since repressed priests and bishops who had arrived in exile prayed along with the clergy of the temple.

In the 1920s, Alma-Ata churches began to be captured by renovationists, by the beginning of the 1930s, only one St. Nicholas Church stood for some time. Here all the mourning and needy were received, fed, washed and given shelter. In the basement, where the lower church in honor of the Dormition of the Mother of God would later be built, there was a Russian stove. Here the exiles were accommodated for the night. The rector then was Alexander Skalsky, one of the most active priests in the city at that time, a brilliant preacher who selflessly helped prisoners and attracted his parishioners to this. He and his colleagues Archpriests Stefan Ponomarev and Philip Grigoriev soon suffered for their faith. All three were arrested in December 1932, interrogated for a month, and then placed in prison in a typhoid cell, which is why they soon died. By the Jubilee Council of 2000, the murdered archpriests of Nikolo-Kuchugur were also canonized.

Old ladies helped to survive

In 1936, the St. Nicholas Church was closed, a museum of atheism was located in its premises, a stable was built during the Great Patriotic War, and soldiers of a penal company were housed in the basement, where exiles used to be saved. Thus, there is not a single functioning temple left in the city. In October 1937, Bishop Tikhon (Sharapov) of Alma-Ata was shot, by the end of the year the Alma-Ata diocese virtually ceased to exist. The issue of reviving church life began to be resolved shortly before the end of the war. In 1944, Kazakhstan was included in the Tashkent and Central Asian diocese. It was territorially too large, and in June 1945, by resolution of the Holy Synod, the Alma-Ata and Kazakhstan diocese was formed, the manager of which was appointed Archbishop Nikolai (Mogilev), who was released early from exile.

He began his episcopal service as Bishop of Kashirsky and then ruled the Tula and Odoevsk diocese, where he fought against renovationism, for which he was first arrested in May 1925. Then he was released several times and soon given a new sentence. In June 1941, the bishop was exiled to Kazakhstan for five years in the remote city of Chelkar; he was brought there by train and dropped off at night on the platform in his underwear and a torn padded jacket. Local old women found him clothes, one of them settled the bishop in her house in a stable, not even suspecting that she was receiving the bishop, and he, out of humility, did not tell her about it. No one wants to hire him, so he was forced to collect alms. He became so weak from malnutrition and hunger that one day he lost consciousness on the street and woke up in the hospital where he was being taken out. After discharge, he began to live in the house of a local resident, an elderly Tatar, who brought him, half-dead, to the hospital. Later, when the spiritual children asked Metropolitan Nicholas why he didn’t tell those who helped him survive that he was a bishop, the bishop answered that if the Lord sends the cross, then He gives the strength to bear it and one must not show one’s will , but to completely surrender to the will of God.

In May 1945, Archbishop Nicholas was released early from exile and in July of the same year, by resolution of the Holy Synod, he was appointed Archbishop of Alma-Ata and Kazakhstan. Arriving at the place, he began to petition for the opening of St. Nicholas Church. And in 1946 it was handed over to the community of believers - without crosses, with destroyed domes and without a bell tower, no iconostasis, no icons. Through the efforts of the archpastor and parishioners, the temple was restored. The Bishop considered the opening of new parishes to be one of the main tasks of his ministry. During his reign, churches and houses of worship were opened. In February 1955, Archbishop Nicholas was elevated to the rank of metropolitan.

He headed the Alma-Ata diocese for exactly ten years, reposing on October 25, 1955. Metropolitan Nicholas wanted to be buried under the altar of St. Nicholas Church, but local authorities did not allow it. All the way from the temple to the cemetery - seven kilometers - people carried the coffin in their arms. About forty thousand people came to say goodbye to their beloved bishop. In 2000, at the Jubilee Council, Metropolitan Nicholas of Alma-Ata and Kazakhstan was canonized and on September 8 of the same year, the holy relics of the confessor were found, which were solemnly transferred to the St. Nicholas Church.

Temple in an adobe house

In the 1930-1950s, one of the most terrible units of the Gulag was located in Kazakhstan - Karlag (Karaganda forced labor camp). Among his prisoners were many Orthodox bishops, priests, monks and laymen who accepted death for Christ. Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian (Fomin), whom many believers know as Sebastian of Karaganda, one of the most revered saints of the Kazakhstan land today, spent six years in prison here.

The future elder was born into a peasant family and was the youngest of three brothers. When he was four years old, his father died and a year later his mother died. Following his middle brother Roman, who took monastic vows in the Optina Hermitage, in January 1909 he became a cell attendant with the Monk Joseph (Litovkin) at the Baptist Skete of the Optina Hermitage. After the death of his mentor, he became the cell attendant of St. Nektary of Optina (Tikhonov). In 1917, he was tonsured into a mantle with the name Sebastian. In 1918, by decree of the Council of People's Commissars, Optina Pustyn was closed, but the monastery continued to exist as an agricultural artel. In 1923, religious services were prohibited and the monastery was closed. Father Sebastian, like most monastics, moved to Kozelsk, where, with the blessing of Elder Nektarios, he began to serve in the Iliinsky Church. He resolutely opposed the Renovationists, maintained contact with the former Optina brethren, cared for many monks and nuns from ruined monasteries who lived in the city, as well as parishioners who had previously visited Optina.

The new government could not like this. In February 1933 he was arrested; When asked by the investigator how the priest felt about the Soviet government, he answered: “I look at all the activities of the Soviet government as the wrath of God, and this power is a punishment for people... You need to pray, pray to God, and also live in love, then Only we will get rid of this.” In order for a priest to renounce his faith, he was left overnight in the cold in his cassock. “The Mother of God lowered such a “hut” on me that I felt warm in it. And in the morning they took me for interrogation and said: “If you have not renounced Christ, then go to prison,” he later recalled his stay in the Tambov OGPU.

Father Sebastian was sentenced to seven years in forced labor camps. First, he was sent to logging in the Tambov region, then transferred to the Karaganda camp, in the village of Dolinka, where he arrived in May 1934. Having gone through the school of the Optina elders, he was also destined to the “theological academy of Karlag,” as researchers of his life write about Father Sebastian.

Due to poor health, he worked as a grain cutter and warehouse guard. During night shifts I never slept, but prayed. The authorities who came to check on him always found him awake. In the last years of his imprisonment, Sebastian’s father was quartered and he lived in a small store, carrying water on oxen for the residents of the Central Industrial Gardens. His spiritual children visited him on Sundays.

At the end of April 1939, Father Sevastian was released, but he did not want to leave Karaganda, he believed that he would be more useful here. He stayed to live in the village of Bolshaya Mikhailovka not far from the city. In 1955, the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared here, which was converted from an adobe house acquired by Father Sebastian and his spiritual children*. A small dome with a cross was built on the roof, but the authorities forbade raising the building; then the priest secretly blessed at night to deepen the floor by a meter. The news about the amazing shepherd spread far beyond Mikhailovka. Monastics and lay people came here from all over Russia for spiritual guidance, and some stayed to live here. Father Sebastian received everyone with love and helped with the arrangement in the new place.

In December 1957 he was elevated to the rank of archimandrite and in 1964 he was awarded the bishop's staff. Before his death, the elder accepted Bishop Pitirim (Nechaev) of Volokolamsk and Yuryev from his spiritual son and tonsured him into the great schema. Bishop Pitirim knew Elder Sebastian from childhood: after the arrest of his father, Archpriest Vladimir Nechaev, Hieromonk Sebastian did not leave him. Vladyka Pitirim also saw off Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian, who died on April 19, 1966 and was buried in the Mikhailovskoye cemetery on the outskirts of Karaganda.

In October 1997, by decision of the Synodal Commission for the Canonization of Saints and with the blessing of Patriarch Alexy II, the local canonization of the Reverend Confessor Sebastian of Karaganda took place. His holy relics were found and transferred to the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Mikhailovka, and in May 1998 they were transferred to the Holy Vvedensky Cathedral, which became the main temple of Karaganda. Once upon a time Father Sebastian blessed it to be built.

By the Jubilee Council of Bishops in 2000, his name was included in the Council of New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church for church-wide veneration.

Today in the village of Bolshaya Mikhailovka you can visit the memorial cell of St. Sebastian of Karaganda.

In 1998, the Mother of God Nativity Convent was created at the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The confessor of the monastery is Archimandrite Peter (Goroshko), who was an altar boy and driver for Father Sebastian. Other witnesses to the righteous life of the saint who live in Mikhailovka are also alive.

Akmola sisters

Forty kilometers from the city of Akmolinsk (now Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan) in the village of Malinovka in 1938, the largest Soviet women’s camp was created - the Akmola camp for the wives of traitors to the Motherland (ALZHIR), a special branch of Karlag. A significant part of the prisoners were repressed as ChSIRs - “members of the families of traitors to the Motherland.” Widows of executed military leaders and famous statesmen of the country served their sentences here. Among them are Ekaterina Kalinina, wife of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Mikhail Kalinin, Anna Larina, wife of Politburo member of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks Nikolai Bukharin, Kira Andronikashvili, actress, film director, wife of the writer Boris Pilnyak, Rakhil Messerer-Plisetskaya, film actress, mother of a ballerina Maya Plisetskaya. Little Maya spent three years in ALGERIA.

Among the prisoners of the Akmola camp were nuns. Evdokia (Andrianova) labored in one of the monasteries of the Moscow diocese, in 1932 she was arrested for three years, then in 1937 for a period of eight years. Nun Evdokia entered the department of Karlag ALZHIR in December 1937. In the camp she was again arrested along with eleven other religious women prisoners who had previously received sentences ranging from two to ten years. In April of the same year, all of them (except Iustina Melanich, who was sentenced to ten years in prison and died in custody) were shot. By the Jubilee Council of Bishops in 2000, nun Evdokia and everyone who was involved with her in the same investigative case were glorified as saints. And today believers pray to the Akmola sisters.

Alma-Ata Calvary

Infamous far beyond the borders of Kazakhstan, Lisya Balka, near the city of Chimkent, became the place of execution and the final resting place of thousands of Orthodox Christians. Among them is Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov) of Kazan, one of the prominent figures of the Russian Church at the beginning of the twentieth century. His spiritual greatness is evidenced by the fact that in 1908, Saint John of Kronstadt, before his death, asked that Bishop Kirill, then vicar of the St. Petersburg diocese, perform his funeral service. In January 1925, three months before his death, Patriarch Tikhon drew up a testamentary order in which he named Metropolitan Kirill the first of three candidates for the position of Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne in the event of his death. Metropolitan Kirill did not have to take up this position. When Saint Tikhon was buried, he was in exile. From December 1919 until his martyrdom in 1937, the Bishop was almost constantly in prison. His last place of exile was the village of Yany-Kurgan in Kazakhstan. In 1937, the archpastor was charged with preparing “an active insurgent action against Soviet power... establishing the patriarchate and the supremacy of the church over state power.” The investigation attributed Vladyka the role of one of the leaders of the “counter-revolutionary organization”, the center of which was in Chimkent. This was the so-called “Chimkent case,” in which sixty-four people—monastics, white clergy, and lay exiles—were convicted and sentenced to death and various terms of imprisonment. Those shot in Lisya Balka, and among them Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov), were immediately buried. At the Jubilee Council of Bishops in 2000, Metropolitan Kirill of Kazan was glorified in the Council of New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church.

An equally mournful place was the Zhanalyk training ground near Alma-Ata, which is called the Alma-Ata Golgotha. Four and a half thousand victims of the Great Terror were shot and buried here; among them are Orthodox clergy, monastics and laity, among whom there are already glorified holy new martyrs. In 2018, a museum in memory of victims of political repression was opened in Zhanalyk.

In memory of the innocent murdered

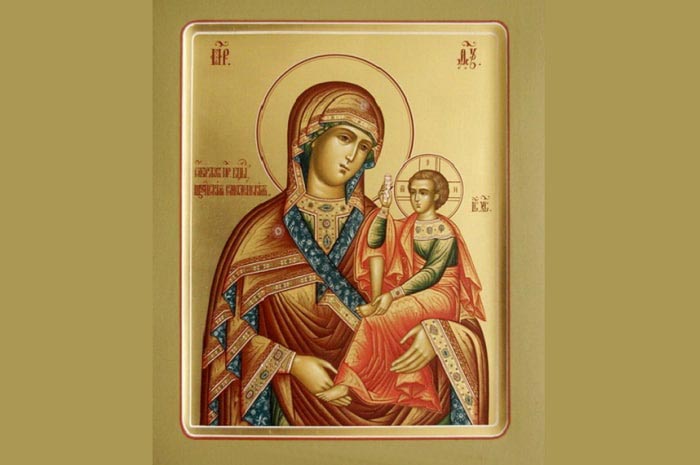

In the 1990s, a lot of work began to perpetuate the memory of those who suffered for their faith on Kazakhstan soil. Today in the Kazakhstan Metropolitan District there are ten dioceses, in which there are 345 churches and nine monasteries. And almost every church has icons with holy images of the new martyrs and confessors of Kazakhstan; they are also depicted on church frescoes. In places of camps, execution grounds and mass graves, monuments, temples and chapels have been erected, where prayer does not stop for thousands of innocent people killed. The Museum of New Martyrs of Kazakhstan operates in Astana. A museum in Almaty is preparing to open in the house where the priest Nikolai Alma-Ata lived.

Research work has been carried out for more than thirty years, thanks to which the names of many who suffered for their faith on Kazakhstani soil were established. In 2018, with the blessing of Metropolitan Alexander of Astana and Kazakhstan and Metropolitan Vincent of Tashkent and Uzbekistan, an electronic database was created on the portal “Turkestan Calvary” about repressed clergy and laity of the Russian Orthodox Church, whose destinies are connected with Kazakhstan and Central Asia, to organize this information.

Maxim Ivashko, an employee of the department for the canonization of saints of the Alma-Ata diocese, says that this year the main work on the project has been completed.

— For five years, members of the commissions for the canonization of saints of the twelve dioceses of two Metropolitan districts and independent researchers from six countries - Kazakhstan, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan - worked to fill out the database, identify and publish the most complete and reliable information about the repressed Orthodox believers of Kazakhstan and Central Asia, corrected inaccuracies and supplemented the lives. The Turkestan Golgotha portal was created to attract new specialists and make the information received available to a wide audience.

The site is forming not only a database, but also collecting literature and sources on the history of the Church in Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The new Internet portal is conceived as a dialogue platform for checking and discussing various data about new martyrs and confessors, collective assessment of compiled biographical information, and a joint search for reliable facts.

Based on the “Turkestan Golgotha” database, we plan to publish a martyrology, which will include the lives of the holy new martyrs and confessors, biographical data of Orthodox believers who suffered for Christ during the years of godless power, who were born, served and committed confessional or martyrdom in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

Those who suffered for Christ

The database was compiled by Moscow historian Sergei Chertkov, an experienced archivist with extensive research experience, editor of a biographical volume of participants in the All-Russian Local Council of 1917-1918, biographer of Archpriest Valentin Sventsitsky and editor of his Collected Works.

— When I got involved in this work, about 500 names had already been identified, mostly those who had been canonized. It immediately became clear that the figure was many times higher, that we were talking about many, many thousands. And to date, we have identified 5,771 people, the website provides a biography of each and indicates sources of information. This is also not a final number. All research on the history of the twentieth century rests on the fact that we only know about rehabilitated repressed people. We know nothing about those who were not rehabilitated (and this is at least one in three, that is, a third) and will not know until the archives are opened again. It must be said that archives have been open in Kazakhstan longer than in Russia, which made it possible to identify quite a lot of names.

— By what principle did you select names for the “Turkestan Golgotha” database?

— These are all those who suffered for Christ and were in some way connected with Kazakhstan and Central Asia: they were born in these parts, served and served exile. These are all those who were in one way or another connected with the Church: not only priests, monks and nuns, but also choristers, watchmen in the temple, elders, who were in charge of some church household. If it is known that a person was not only a parishioner, but led an active church life, participated in the church “twenty”, or was a scholar who wrote works on theology, or was convicted under a criminal article for religious preaching or agitation, we included such people. If the interrogation involves a person’s direct connections with the Church, then, of course, we took this into account. They also included the catacombs and Old Believers in the database.

Repressed people who died outside communion with the Church are included in a separate section; There were 85 such people. These are those who have deposed themselves or transferred to the “Living Church”. We also decided to take them into account, since one way or another they are churchgoers, baptized, Orthodox people. We tried to present this information very carefully, since it was known for sure about some that he had converted to the Living Church, and about others with a greater or lesser degree of probability. So it is with those who left the rank. If a person who has removed his rank publishes in the press that he is no longer a priest and renounces Christ, then we consider him to have fallen away. In Kazakhstan, newspapers from the 1930s are well digitized, where a note about renunciation also included a denunciation of other people, naming specific names. It was not enough to renounce; one also had to sign in blood. Such articles confirmed that those who were denounced definitely lived in Kazakhstan at that time, were connected with the Church and did not renounce it, for which they were subjected to repression. We started looking for them, found them among the repressed and included them in our database.

In the mid-1920s, there was a massive campaign against the renovation of icons, even leading to lawsuits. The central press - Pravda, Izvestia - published notes that thirty people had been arrested somewhere on charges of falsely updating icons. Then we look for the names of these people in the documents and find them among those exiled to Kazakhstan. And these are ordinary peasants who either stood up for the icon or were parishioners of the temple. We also included such people in the database because they were involved in church business - parishioners who talked about updating icons or began to venerate such an icon as miraculous. Usually dozens of people were involved in these cases. Back then, people were not so intimidated and openly expressed their opinions and spoke the truth. In the 1930s this became no longer possible.

Archives helped

— How did you collect information on each person?

— We worked in archives. A huge number of cases have been declassified and transferred from the FSB archive to the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) for free access, which is located in Moscow. We received some information from the Russian State Historical Archive (RGIA) in St. Petersburg. I was probably the last archivist researcher from the Orthodox community who was allowed into the Central Archive of the FSB of Russia, since I had accompanying papers from His Holiness Patriarch Kirill.

The most difficult thing is to trace the pre-revolutionary biography of the clergy. To do this, it was necessary to re-read all the regional “Diocesan Gazette” for 30-40 years, which were published from 1860 to 1922 in 63 dioceses of the Russian Church, and find these people in them, learn about all their movements.

We also actively used the archival database on the First World War. It is rarely used by anyone, not only among church historians, but also among secular ones. And it is exceptionally well compiled and is in the public domain because it is posted on the Internet. It lists all those awarded, all the wounded, all those killed in the First World War. And this is important information for clarifying the pre-revolutionary period in the biographies of convicts. For example, we found out how many future priests went through the First World War, became heroes and were awarded, and then, already in the 1920s, they were ordained. This says a lot about a person who went through the war. What can I say, sometimes it turns out that during the war a person lost an arm and, being disabled, served the Church, for which he was repressed and shot.

Of course, they used the base of Sergei Vladimirovich Volkov, our most important historian on the Civil War and the White Movement, from which they learned that many future priests fought in the Civil War, on both sides. And it even happened that in one battle they launched a bayonet attack on each other. And then, in the 1920s, they took holy orders and in the 1930s both were shot.

— Were relatives of those repressed involved in the search?

- Yes, we announced that such a database is being compiled, please contact us. Letters were sent from relatives, they began to send photographs, various other testimonies, and memories. In the 1990s, one of our relatives managed to copy the criminal cases that they shared with us. Unfortunately, there were few relatives of the repressed; in those years, almost the entire family was cut to the roots; as a rule, only ten percent survived. And how many years have passed, few of the witnesses have survived to this day. Therefore, each such testimony is priceless.

It was possible to restore the lives of quite famous people after their release from prison. After all, usually standard biographies in databases on repressed people end like this: repressed, ten years - and that’s it. And many of those convicted survived this period, returned and lived on, sometimes living a long life and participating in the affairs of the Church.

And of course, we contacted the dioceses and metropolises of other states - Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, and they also helped us there. So, through joint efforts, we compiled this database.

This year added a new saint

— And who made up the largest percentage of those repressed?

- Nuns who were convicted in the early 1930s and received the standard sentence - three years of exile in Kazakhstan. There are about one and a half thousand of them. Most of them died, even unable to withstand this three-year exile, because it was hell. And the nuns were mostly elderly. They were transported, like all other prisoners, in a cattle car with only four walls and a ceiling. We traveled for several days, and ten percent of those transported died along the way. Those who survived were thrown either into an open field or into some small settlement. No work, no salary, no security. Live as you wish, on bare ground. Good people sheltered some, and some built shelters from cow dung and lived in them. Two thirds died in the first years of exile.

Those who survived received a second term. But at least a third of them returned from these exiles and continued to live church life in the 1940s and 1950s.

— What were the difficulties in clarifying your biographical data?

— Often in the biographies of convicts there is an error in the verdict. It is written that three years of exile in Kazakhstan. You start to figure it out and find out that in the end the man was exiled to the North, to Arkhangelsk. In those years, it often happened that the sentence changed from south to north, as well as vice versa. A person is sentenced to exile in Kazakhstan, but the Kazakh territory intended for prisoners is overcrowded, and the sentence was changed and sent to another place, as a rule, to the North - to Arkhangelsk, to Murmansk.

— There are probably no such number of new martyrs as in Kazakhstan anywhere else?

- Yes. In Siberia, for example, it is much less. This is understandable. Siberia was set aside for deportation during the collectivization period in the late 1920s and early 1930s; more peasants and kulaks were sent there, and more believers were sent to Kazakhstan.

In August of this year, a new saint was glorified - Archpriest Vasily Nosov. He was canonized by the Chelyabinsk Metropolis because he served there and suffered for his faith. But we also consider him ours, Kazakhstani, since before the revolution he served in the Kustanai district. Therefore, they included it in the “Turkestan Golgotha” database.

— Do you have any memorable fates of convicts?

— As a rule, when I was working on the base, my working day was like this: I sat down at the computer in the morning and at nine in the evening I got up from it and went to tell my family about what amazed and shocked me. And this happened almost every day. Just look at the stories about how future priests fought! I remember one fantastic biography when a man ran three times - twice from the stage, once from the zone - and was caught each time. There are a lot of such stories. You can write a book.

Elena Alekseeva

* Adobe is a building material made from a mixture of clay soil, straw, sand and water.

The time of persecution of the twentieth century revealed to the world a host of martyrs, confessors and devotees of piety, who embodied with their lives the highest moral ideal of Christianity and gave us an example of moral perfection, courage, and an unclouded vision of the eternal meaning of life. Their life, their firm stand for the faith were the salt of the earth (see Matt. 5:13) and the light of the world (see Matt. 5:14), helped the Church pass through this historical period of time.

The Council of Kazakhstan New Martyrs and Confessors united the faithful sons and daughters of our Church from various provinces of the former Russian Empire - from the Baltic and Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean. The martyrology of the Great Steppe contains the names of such famous hierarchs as Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov) of Kazan - an unbending, uncompromising fighter for the holiness and purity of Orthodoxy; Archbishop of Simferopol Luka (Voino-Yasenetsky) - a world-famous surgeon, professor of medicine, Stalin Prize laureate, author of many unique scientific works; Archbishop of Kostroma Nikodim (Krotkov), Archbishop of Omsk Alexy (Orlov), Archbishop of Voronezh Zachariah (Lobov), Bishop of Lipetsk Uar (Shmarin), Bishop of Ivanovo Boris (Voskoboynikov), Bishop of Dmitrov Seraphim (Zvezdinsky), Archbishop of Kherson Procopius (Titov), bishop Podolsky Ambrose (Polyansky) and many others. Wherever an Orthodox Christian lives today - in Central Russia, the Far East or in Siberia, Ukraine, the Baltic states, Belarus - his diocese, parish, native church will always be connected in a special way with Kazakhstan by the name of one or another sufferer of Christ who shed on this land their blood or those who served prison sentences here in exile and camps.

Without any exaggeration, the land of Kazakhstan can be called blessed. Having become a place of martyrdom for hundreds of thousands of believers, stained with the blood of sufferers, washed with the tears of the innocently condemned and watered with the sweat of ascetics, our country has become the spiritual treasury of the Orthodox Church. According to the Venerable Elder Sebastian (Karaganda), “day and night here, on these common graves of martyrs, candles burn from earth to heaven.”

On the blessed land of Kazakhstan, every church celebration and every Orthodox holiday is inextricably linked with the memory of thousands of new martyrs and confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church who suffered here for Christ in the 20th century. The sufferers of Christ - hierarchs and priests, monks and laity - carried the light of Easter into the dark prison dungeons, spread it across the vast Karaganda steppes and in the gorges of Alatau, generously shared it with embittered and despairing souls, revealed it to those who had not heard the gospel of Christ before . And now, fully enjoying the contemplation of this light, they call on us to share their bliss.

Militant atheism gave rise to prisons and concentration camps, torture and abuse, and millions of innocent lives were sacrificed to the atheistic regime. But in the last open Orthodox churches, in the houses of believers, in cells and barracks, prayers continued to be offered to God, the words of the Holy Scripture were heard, and the Divine Liturgy was served. Surrounded by spiritual darkness and the criminal muteness of apostasy, surrounded by the horrors of the camps and false witness, the Church lived and carried its unquenchable lamp of faith.

Honoring the memory of the holy martyrs is not only the sacred duty of a Christian, but also a blessed opportunity to take advantage of the fruits of their selfless deeds, to acquire their virtues, the main of which is love for God and neighbor. Let's not neglect this opportunity.

Metropolitan Alexander of Astana and Kazakhstan